By Katie Barlow

on Oct 20, 2020 at 8:50 pm

This article is part of a symposium on the jurisprudence of Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett.

Ten years before Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the landmark Second Amendment opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller crystallizing the Constitution’s guarantee of the right to keep and bear arms as an individual right, he was welcoming a young clerk to chambers by the name of Amy Coney Barrett. There were no Second Amendment cases before the Supreme Court that term. In fact, before Heller, the court had not taken up a Second Amendment case since 1939 — and before then, only twice in history, both in the 19th century.

The court has decided three Second Amendment cases since Heller in 2008, and if Barrett takes the bench, it’s possible the court would be inclined to again revisit – and potentially further expand – gun rights. Some scholars say the former Scalia clerk may be willing to go to the right of her former boss on guns.

Conventional wisdom suggests that the four most conservative justices on the current bench – Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh – would like to take up more Second Amendment cases. Thomas, in particular, has written that the court gives short shrift to the Second Amendment when compared with other rights. And Kavanaugh wrote last term – in a concurrence to a 6-3 decision finding that a challenge to a New York City gun-safety law no longer presented a live case – that the court should take up another Second Amendment case “soon.”

Four votes is enough to take up a case, and the court has had plenty of opportunities to do so. At the end of last term, the justices spent weeks considering 10 different cert petitions in gun-rights cases but ultimately declined to hear any of them. Some court watchers believe that some members of the court’s conservative wing became hesitant to accept new gun cases because they were unsure of how Chief Justice John Roberts would vote on the merits. Barrett would change that calculus as a justice likely to take an expansive view of Second Amendment protections.

That’s reading the tea leaves, though, when there’s really only a pinch in the cup. Barrett has written only one opinion on the Second Amendment during her three years on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit. It was a dissent.

The case was Kanter v. Barr. Notably, the questionnaire that Barrett submitted to the Senate Judiciary Committee requested that she list her “most significant cases.” Kanter got top billing.

Rickey Kanter was convicted of a single count of felony mail fraud for defrauding Medicare in connection with therapeutic shoe inserts. He challenged federal and state dispossession laws that prohibited him from owning a gun because he had been convicted of a felony. Kanter argued that those laws violated his Second Amendment right to bear arms. A three-judge panel from the 7th Circuit disagreed with Kanter 2-1 — with two Reagan appointees in the majority.

In her dissent, Barrett sided with Kanter. She suggested that, when assessing the constitutionality of gun restrictions, courts should look to “history and tradition” to see whether there is a historical precedent for the restriction at issue. Under that test, only restrictions with historical analogues would be upheld as permissible under the Second Amendment. Barrett’s history-first approach differs from the test adopted by most lower courts in the wake of Heller. Most courts have assessed gun laws not by looking at history but by analyzing the government’s asserted justification for the law and comparing that justification with the law’s effects – a two-pronged test that the Kanter majority described as “akin to intermediate scrutiny.”

Barrett’s dissent echoed a similar dissent that Kavanaugh wrote as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, before President Donald Trump nominated him to the Supreme Court. In that dissent, Kavanaugh argued that “history and tradition,” rather than the standard “intermediate scrutiny” test, should guide courts when assessing the constitutionality of gun laws. If Barrett is confirmed, the court’s two most junior justices could find themselves as long-term allies in steering how lower courts approach Second Amendment rights. They likely would be joined by Thomas, a strong originalist who recently lamented that many lower courts have “resisted” the history-based approach.

Scholars view the “history and tradition” test as generally leading to more expansive gun rights. And indeed, in Kanter’s case, Barrett performed a lengthy review of 18th and 19th century gun laws before concluding that a categorical ban on gun ownership for all people who have been convicted of a felony is unconstitutional. “History is consistent with common sense: it demonstrates that legislatures have the power to prohibit dangerous people from possessing guns,” she wrote. “But that power extends only to people who are dangerous. Founding-era legislatures did not strip felons of the right to bear arms simply because of their status as felons.”

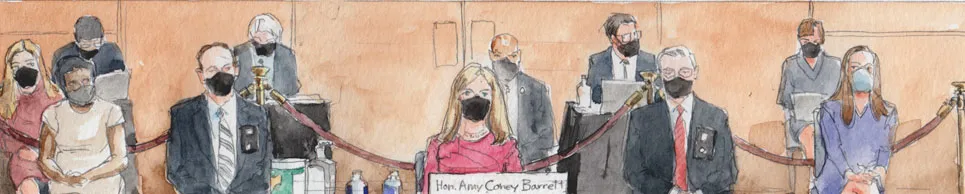

During Barrett’s nomination hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week, Democrats repeatedly pressed her on her Kanter dissent and her views on the Second Amendment more broadly. She did little to elaborate on her views beyond repeating the reasoning laid out in her dissent.

One thing she did divulge – in response to a question from Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) – is that her family is among the roughly 40% of American households that own a gun. She pledged to decide any Second Amendment case without regard to her personal views on gun ownership, and she said she would come to the court with no agenda on the issue.

Among the 10 gun-rights cases that the court declined to hear this summer was a case about whether states can ban assault rifles and large-capacity ammunition magazines. That denial may have been a different story with a Justice Barrett on the bench. As it happens, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in August struck down a California ban on large-capacity ammunition magazines as unconstitutional. According to Professor Stephen Vladeck of the University of Texas School of Law, that case could be like “candy” for a newly solidified conservative majority if Barrett gets confirmed.